Prototyping AI ethics futures: Data, AI and environment

Recently, the Ada Lovelace Institute conducted a week-long series of events highlighting the new possibilities of a humanities-led, broadly engaging approach to data and AI ethics. Within this, the Institute held a conversation on ‘Prototyping AI ethics futures’, joined by our CEO Jaya Chakrabarti, with Caroline Ward, Erinma Ochu, Jennifer Gabrys & held by Teresa Dillon, in partnership with The British Academy and Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

Ada Lovelace Institute took to twitter to give a commentary on the topics discussed in the event, summarising the points mentioned. You can find the full video of the event at adalovelaceinstitute.org.

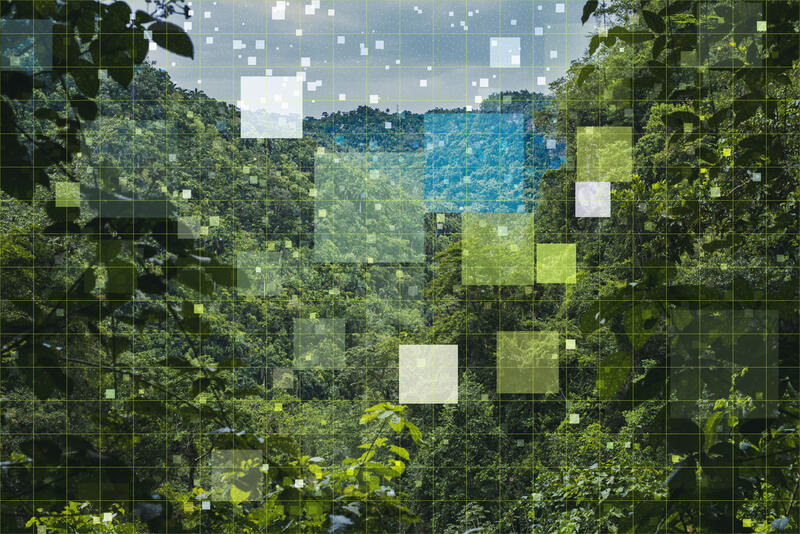

Professor Jennifer Gabrys kicked off the conversation, discussing the Smart Forests project, which investigates the social-political impacts of digital technologies that monitor and govern forest environments. The Smart Forests project is designed to consider the implications of data and AI within spaces of environmental management & governance. Jennifer speaks about how forests around the world are becoming increasingly digitalised, the importance of forests in the current climate and how technology can be used to monitor deforestation and the movements of supply chains. Dr Gabrys explains that the key research question of the projects is: How do Smart Forests shape environmental governance, civic engagement and social-political strategies for addressing environmental change? Jennifer also touches on the darker side of forest tech, discussing potential damage and inequalities that could be introduced by the changes governed by digital technologies. For example, there may be forms of participatory mapping that bring in Indigenous voices and ensure that they are not displaced by extractive industries.

This topic followed on to discussions of afforestation with data via our platform, Vana. CEO Jaya Chakrabarti spoke about the value of open data, describing data transparency as “a foundation upon which we can get meaningful change”. By highlighting the role that corporates have to play in both accelerating the climate crisis, and in contributing to the UK climate response, transparency may help apply pressure to those companies that hold all the power. “We know that good policy is dependent on good data. And we know that bad data can destroy lives when it comes to policy. We have seen it happen time and time again.”-@jayacg. Simply by making ownership more visible to the corporate heart, we can enable landowners to re-evaluate the effectiveness of their own land use in the context of global warming. More land *should* mean more effective land use to combat our climate emergency.

In response to Vana’s mission, as outlined by Jaya, Erinma Ochu and Caroline Ward (collectively @Squirrel_Nation, and @justainet Fellows working on AI & racial justice) discuss the social impacts surrounding planting trees within communities. Erinma and Caroline highlight the resistance to tree planting initiatives in a Detriot community when a local nonprofit came to plant trees on their block. A local resident commented “come in and try to ‘do good,’ but only half do the job.” The main point to take away from this is that, when planting trees, residents feel that the government bodies or organisations responsible must continue to maintain upkeep of the trees following planting.

The conversation then moved to being centered on some of the effects of not consulting with communities affected by environmental and/or tech projects, and “where power lies in decision-making.”

Teresa Dillon proposed a final question: Do you see the possibility of your efforts as a potential decentering of the human in this entanglement that we’ve had, where we’ve been prioritizing ourselves first and foremost above other species? Where are the efforts that you see most needed?

Jaya responded that, for her “it is about acknowledging that human beings have very different roles, and we have all of these roles to bring to address the issue. The technology that we are bringing into play should enable a human being to be that human being [with] their own agency. But also [recognising] that they are an employer or employee, a family member, a consumer. I think it’s about enabling them to use the power that they have and connect up with those different identities. I would hope that technology could be used to humanise things more.” Jaya concluded that, from her perspective “the aim is to humanise.”

Dr Gabrys summarised by stating that “human induced climate change” is a problematic term. Dr Gabrys believes that climate change has been induced by a “particular kind of human, that has lived in the world in particular ways and often those ways involve domination over other entities.” She went on to highlight the importance of thinking of a human as a verb and not a noun, as these projects involve thinking about how to become a human who is in relation with other entities without having to be extractive. She discussed “being planetary as a practise” which means to ask how planetary could also be a verb. It is not just a static governed object, but is always in the process of becoming and of making demands of us.

Squirrel Nation summarised the challenge as the “conjunction between who gets to be human and who doesn’t.” Erinma Ochu and Caroline Ward linked environmental issues to those in the social world, such as racial capitalism, and suggested that we may need to put in place refusal around some of those technologies used to manage world issues.

The Ada Lovelace Institute highlights the point that data-based technologies ‘instrument’ our relationships with other living things, and with the collective basis of our environment.

Jaya comments: “These discussions help us to evaluate Vana’s role in the application of data to help solve climate issues against the potentially unintended consequences highlighted by ethics researchers in this field. Our goal is the prevention of harm whilst enabling more good after all. I am grateful to the Ada Lovelace Institute for having the foresight to facilitate these discussions.”

By overlaying data relating to corporately available land with land that is suitable for tree planting, Vana has identified areas across the UK to be used for afforestation and can help pair landowners up with environmental groups to make the most of the land opportunities we have.